Mesalamine (and select probiotics) keep Candida at bay during antibiotics by supporting gut hypoxia

Note: This post was first written in September 2023 in response to a preprint by the Baumler lab and updated in August 2024 to include the full published findings.

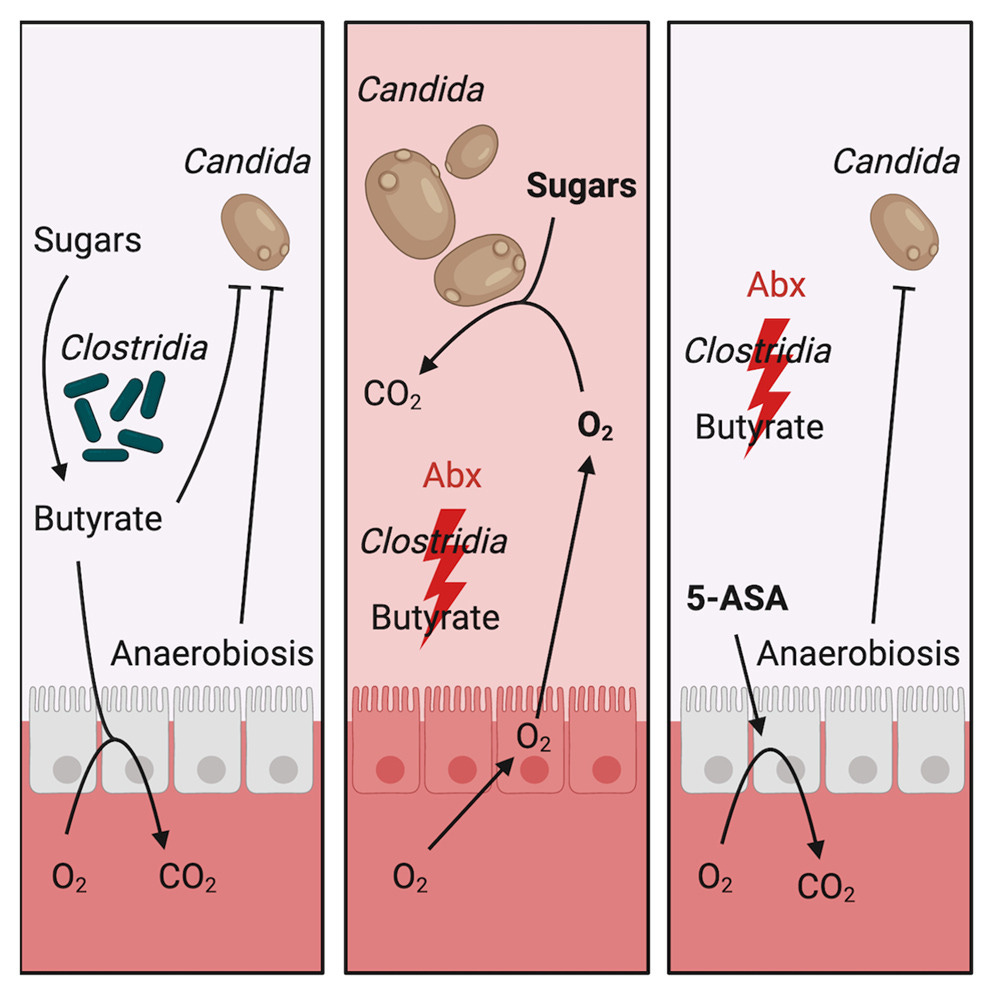

A healthy colon is a low-oxygen environment. In my blog article on the oxygen-gut dysbiosis connection, I explained how:

Beneficial bacteria like Clostridia produce butyrate, which helps keep oxygen levels low.

Antibiotics deplete Clostridia and reduce gut butyrate levels, causing a shift in gut epithelial cell metabolism.

This metabolic shift increases the release of oxygen, lactate, and nitrate into the gut lumen, which can upset the balance of the gut microbiome, leading to dysbiosis.

Activating a specific pathway in gut epithelial cells, called PPAR-gamma, can reverse this dysbiosis by promoting butyrate metabolism and oxygen utilization.

Mesalamine (5-ASA), a medication commonly used to treat inflammatory bowel disease, is one such PPAR-gamma activator.

A recently published study from the Baumler lab suggests that mesalamine (5-ASA) can also help prevent Candida albicans (yeast) overgrowth after antibiotics by maintaining low oxygen levels in the gut.

In the study, antibiotic treatment in mice depleted Clostridia, increased gut oxygen levels, and disrupted the ability of the gut to resist colonization by C. albicans. Supplementing with Clostridia or treating with mesalamine restored gut hypoxia and prevented C. albicans overgrowth.

This is important because broad-spectrum antibiotics are a common risk factor for Candida overgrowth. While antifungals are sometimes prescribed alongside antibiotics to prevent this, they are also broad-spectrum and can negatively impact beneficial fungal populations.

New findings on E. coli Nissle 1917

The study also explored the use of the probiotic E. coli Nissle 1917, finding that this probiotic could also prevent Candida overgrowth. While Clostridia do this by producing butyrate, E. coli Nissle 1917 does it by consuming oxygen in the gut, creating conditions that are less favorable for Candida to grow.

This finding is significant because it suggests that certain oxygen-consuming probiotics, such as E. coli Nissle 1917, could potentially be used alongside mesalamine and butyrate to help protect gut health after antibiotic treatment. The combination of these approaches could provide a multi-faceted defense against antibiotic-induced dysbiosis and Candida overgrowth, especially in people who are at high risk.

However, the broader implications of using high amounts of E. coli Nissle 1917 during or post-antibiotic treatment remain uncertain. While it might help restore hypoxia, there’s also a possibility it could come to occupy too large of a niche in the gut and/or delay the return of other beneficial bacteria - a phenomenon that has been observed with other probiotics.

Exploring Saccharomyces boulardii as an alternative

Prompted by these findings, I considered whether other oxygen-consuming probiotics might offer safer alternatives. You may recall that I initially suggested caution against all probiotics after antibiotics, but hypothesized that Saccharomyces boulardii was likely to be the least harmful.

More recent research now suggests that S. boulardii (particularly the strain in Florastor, CNCM I-745) might uniquely facilitate microbiome recovery post-antibiotics. Notably, S. boulardii also increases PPAR-gamma expression and utilizes available oxygen, much like the probiotic E. coli in the study I discussed above. It also produces acetate in oxygen-rich conditions, which may help to support gut ecosystem recovery.

To date, there has not been a robust study (involving metagenomics and extended monitoring) of post-antibiotic microbiome recovery with and without S. boulardii. I’d love to see that data! Nevertheless, increasing evidence points to it as a good option.

Takeaways

The optimal strategy to support a healthy gut during and after antibiotics is likely a combination of butyrate, S. boulardii, and mesalamine (if possible), especially for those at high risk of Candida infection. Future research will hopefully confirm these findings and determine the optimal dosing and timing of these measures.

Would this also lower D-lactate in the stool? Thanks